In the seemingly ever-lasting search for economically-viable superconductors, a variety of scientists and researchers have published findings on naturally-occurring mineral miassite as an “unconventional superconductor.” These findings (“Nodal superconductivity in miassite“) were published for Open Access viewing on Nature.com and include contributors from a variety of US universities, as well as institutions in France and New Zealand.

Unlike semiconductors, which are still integral to the overwhelming majority of modern electronics, superconductors are capable of conducting electricity with 100% efficiency, not losing any power (typically released as heat) in the process. They can also create permanent magnetic fields. This pretty much makes economically-viable superconductors a proverbial “golden goose,” should anyone ever actually achieve the seemingly-impossible goal of finding or creating a material that behaves this way at or near typical room temperature.

Fortunately, the findings of a superconductor as a naturally-occurring mineral (with some caveats, of course) in this “Nodal superconductivity in miassite” paper seems to be a step in the right direction for this research. According to the paper, miassite functions as a superconductor at 5.4 degrees Kelvin, or -449 degrees Fahrenheit. So clearly there will still need to be some major temperature lowering involved.

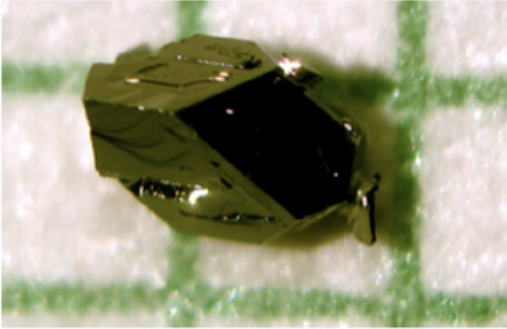

Miassite is a mineral that can be both found in nature and synthesized in a lab. In its clean synthetic form, it is the only mineral so far that exhibits unconventional superconductivity. The form found in nature may be capable of this, but researchers note that it is unlikely because of “unavoidable impurities that quickly destroy nodal superconductivity”.

Additional statements on the paper from Ames National Laboratory (who participated in the original paper) elaborate that “Uncovering the mechanisms behind unconventional superconductivity is key to ecnomically-sound applications of superconductors”. The full paper details how miassite was evaluated by the researchers to come to the conclusion that it is, in fact, a viable superconductor.

The reason it took so long for this discovery to come about is because of the aforementioned impurities that naturally occur in the mineral as it appears in nature. Near the end of the paper, the researchers note “Nature knows how to hide its secrets”— fortunately, lots of educated and talented humans enjoy uncovering those same secrets.

While sometimes-dubious claims like room-temperature superconductivity or field-tunable superconductors remain a hot-button point of debate, the discovery of a (mostly) naturally-occurring superconductor offers a promising new angle for future superconductor advancements.