Did you know that the discovery of helium, an element we immediately link with balloons, has an Indian connection? Here, a performer floats in the air with supporters attached to helium balloons.

| Photo Credit: AFP

What on Earth does a gas that we normally associate with balloons have to do with Guntur, a city in Andhra Pradesh? Everything, apparently! Though, to be absolutely clear, it must be stated that it all started with observations of the sun from Guntur, before the existence of helium on Earth was ever discovered.

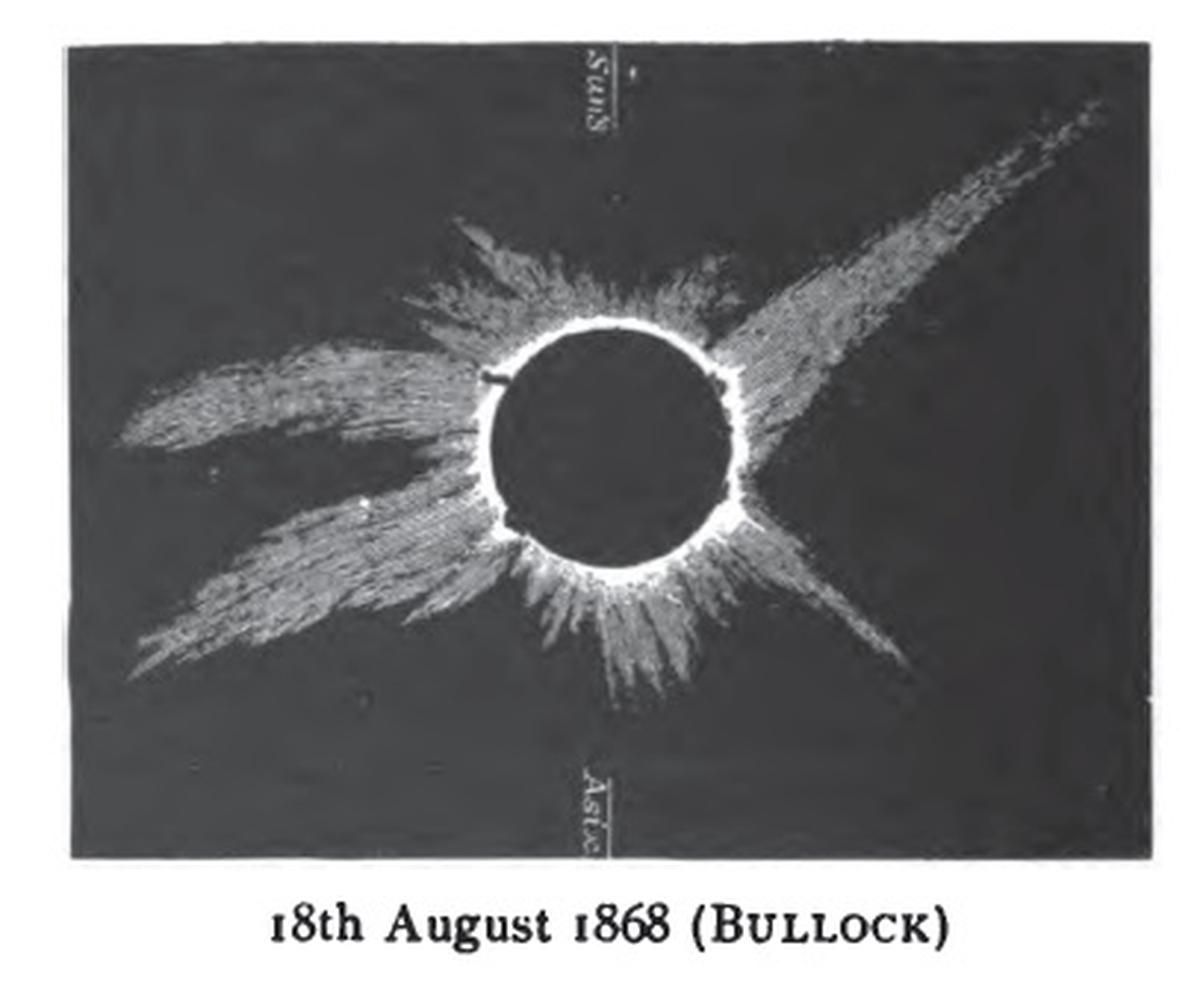

A sketch of the 1868 eclipse.

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

Making up nearly a quarter of all matter in the universe, helium is the second-most abundant element in the cosmos, behind only hydrogen. Despite this, helium is rather rare on Earth, only given off as a product when heavier elements undergo radioactive decay. Unless it is produced deep underground or trapped within rocks, the ultra-light non-reactive helium usually flies off and vanishes into space.

Spans decades

The story of the discovery of helium is a long, drawn-out one that spans the major part of an entire century. While the Guntur episode is an important one, it comes somewhere in the middle of the entire story. To begin with, we would have to step back over two centuries to 1814.

A lot of information regarding a substance and its structure can be arrived at by studying the light absorbed or emitted by it. With their ability to disperse light into measurable wavelengths, spectroscopes were about to change the way scientists studied the chemical composition of nearly everything.

Fraunhofer lines

Using an early version of a spectroscope, German optical lens manufacturer and physicist Joseph von Fraunhofer created a spectrum broad enough to notice dark black lines interrupting the normal colours. While he didn’t understand what they were, they now bear his name (Fraunhofer lines) and it set the ball rolling with regard to studying spectral lines to better understand substances.

By 1859, Germans Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen mastered the art of using the analyses of light to figure out the chemical composition of the sun and the stars. The physician-chemist duo, credited with the invention of the modern spectroscope as we know it today, discovered that elements produced bright lines of light in the spectroscope when heated, and that these lines sometimes corresponded to the Fraunhofer lines.

Make a beeline for India

With the understanding prevalent then suggesting that the sun’s spectrum could only be observed during an eclipse, astronomers were eagerly awaiting the total eclipse predicted for 1868. As the eclipse was to have nearly six minutes of totality – a long time in the context – it afforded plenty of observational time. The path of totality passed through the breadth of India, forcing the scientific community world-over to make a beeline for the country.

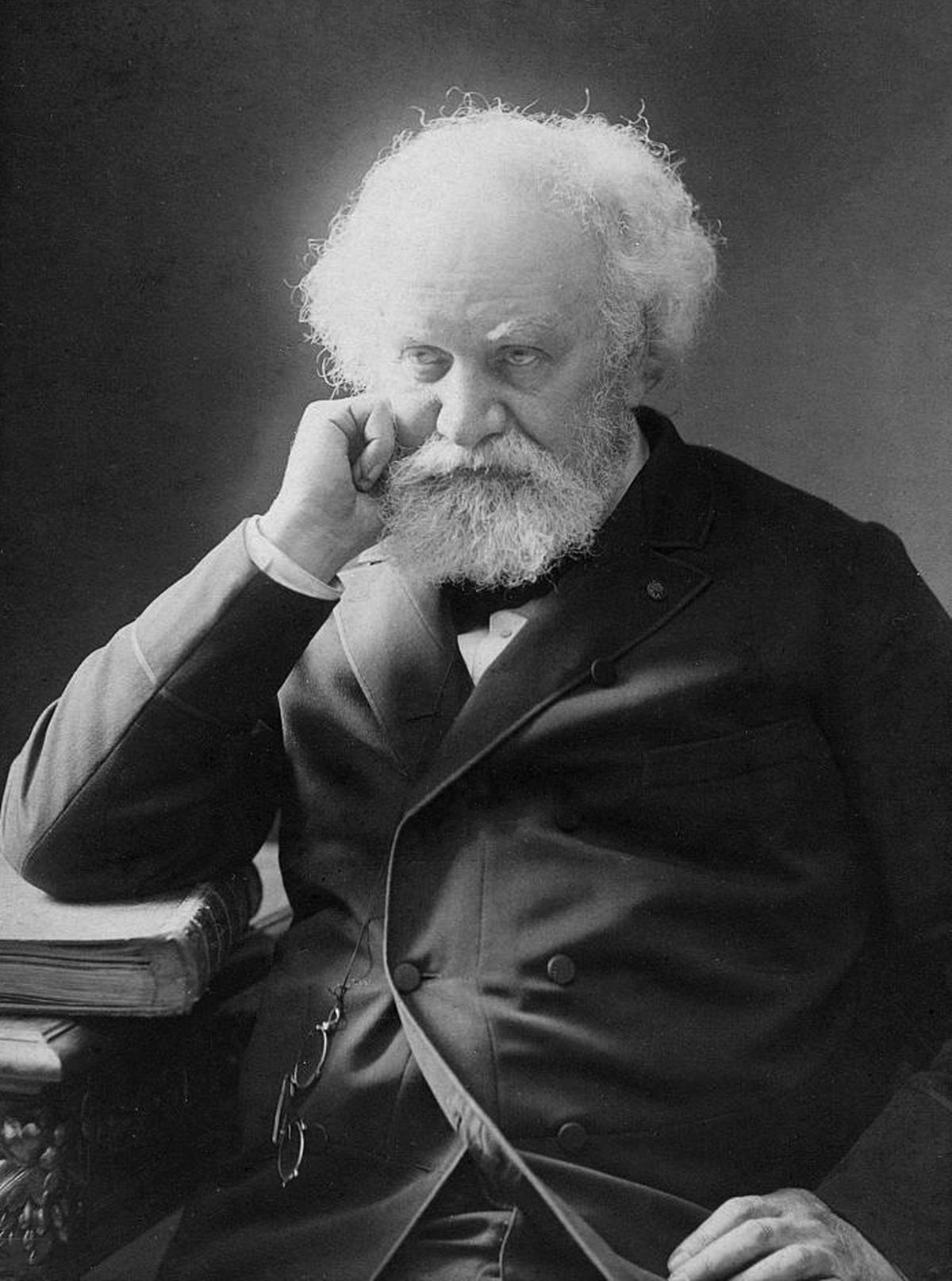

French astronomer Pierre Jules Cesar Janssen.

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

Among them was French astronomer Pierre Jules Cesar Janssen, an eclipse chaser who had already made his name in the field of solar spectrum. While British astronomer and director of the Madras Observatory Norman Pogson headed to Machilipatnam (a city now in Andhra Pradesh), Janssen and another British team made their way to Guntur. In addition to the coastal nature of Machilipatnam and hence the risk of fog and cloud, Janssen’s decision to choose Guntur could well have had to do with the fact that the place had been under French rule and was still teeming with French merchants.

An unusual spectral line

The eclipse occurred on August 18, 1868 and it was well observed by the various teams positioned in different parts of India and elsewhere. A few days later, Pogson’s observation of something unusual – a spectral line close to that of sodium, but not quite the same – reached the astronomical circles.

Janssen rightly made the prediction that the line likely belonged to an element never seen on the Earth before. He also realised that using a modified spectroscope, it should be possible to view the spectral lines of the sun on any given day, without having to wait for an eclipse to take place.

In sync with each other

At about the same time as Janssen was making these giant strides towards the discovery of helium, Joseph Norman Lockyer, a London-based civil servant and amateur astronomer with a great interest in the sun, was independently arriving at the same results. Either on the same day, or within days of each other in October, the French Academy of Sciences received scientific papers from both men, revealing their work that would allow viewing solar prominences without eclipses, and the possibility of having likely spotted a new element.

Sir Joseph Norman Lockyer.

| Photo Credit:

Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images / Wikimedia Commons

Rather than try and find out if the credit was due to be given to just one of them, it was decided that both men will share the merit of their findings, with each one’s work confirming that of the other. That, however, didn’t imply that they had won over the confidence of the entire scientific community and they did receive flak for their suggestion that the spectral line could belong to an alien element.

Ramsay’s discovery

Even though Lockyer went ahead and named the element helium, it took more than 25 years for that element to be finally “discovered” on Earth. The credit for that goes to Scottish chemist William Ramsay, who not only isolated helium while working with an ore of uranium in 1895, but also showed that it was a product of the radioactive decay of radium.

In the years since its discovery, helium has been shown to serve many important purposes. Yes, helium gas can be used to fill in balloons that are more versatile and durable than air-filled balloons. The element is also used in medical machinery like MRI scanners, semiconductor manufacturing, cooling, and of course, meteorological balloons as well.

Published – August 18, 2024 12:14 am IST