It is customary to refer to childhood as a ‘golden’ period of existence, a time of idyllic innocence and unadulterated joy. But the griefs, troubles and cruelties one experiences in childhood are just as much traumatic then as the pain caused by incidents in later life. For a child, the loss of a pencil may be as earth-shattering as the loss of a diamond ring for an adult. The circumstances may differ but the intensity of the grief is real. Children can be unkind too, and harbour resentments and desire for revenge, even wishing death for their tormentor or for themselves. So many of us look back at our childhood and luxuriate fondly in memories of people and incidents that may sometimes never have happened or have happened differently than what we remember later. Is that some sort of a defence mechanism that the mind fashions, perhaps?

Maria’s story is made up of layers of memories — not only her own but of other members of her extended family as well. The narrative has multiple chroniclers and time weaves in and out, fusing past and present, imagination, dream and reality in its path. The reader is confronted with the notion of ‘madness’ and ‘normalcy’ as they flow seamlessly into each other. Who is mad, and who is not — and who is to judge and decide?

Village life in Kerala that moves with the rhythms of a bountiful Nature is brought to life in the novel as are the various characters, and the traditions of the household. Underlying it all is the humour in the descriptions, the quirkiness and foibles of people — and love. Narrated partly through the eyes of Maria as a child, there is a deftness to the point of view that evokes her innocence and coming of age as she moves through life having conversations with dead people, her dog, Chandipatti who has a penchant for philosophy, and God. In spite of the humour, there is a seriousness to the account as it touches upon environmental change, patriarchy, politics and kindness towards animals, and of course, relationships, and the state of the human mind. It also taps into the world of magic realism with a description of how the patron saint of the area gets bored and begins to enter the dreams of people — to name just one — so skillfully brought into the plot that it is accepted just as other, more real worldly events are.

The translation flows flawlessly. The translator brings in the ethos of the setting with the masterful use of Malayalam words (for foods, honorifics, etc.) while displaying a command over English that reads lucidly. The story sways to a music that is a fusion of Malayalam and English tones, drawing the reader into the universe that is ‘Marian’, as the protagonist navigates and negotiates for her place in it. The transcript of a conversation between the author and translator at the end is interesting as it discusses the creative process, the characters, and the choice of theme.

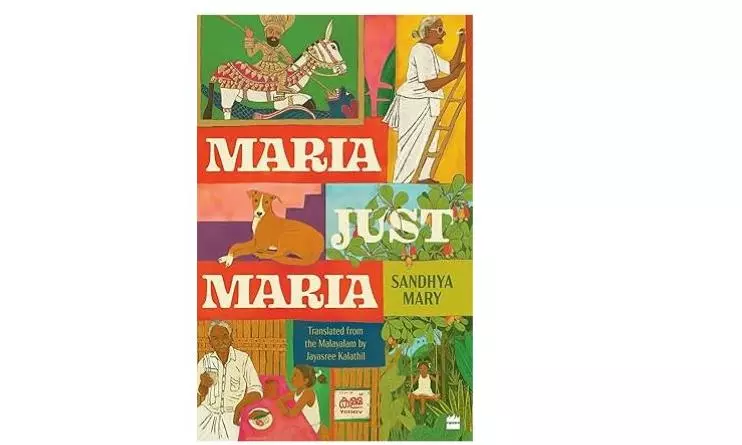

Maria Just Maria By Sandhya Mary Translated from the Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil Harper Perennial 2024 pp. 232; Rs 499