Hyderabad: The rampant rise in encroachments around the historic Golconda Fort has heritage activists worried. They fear that this adverse trend will further diminish the chances of the monument — along with the Charminar and Seven Tombs — of getting Unesco’s World Heritage tag.

The three Qutb Shahi structures have collectively been on Unesco’s tentative list for years now. They have, however, failed to make the final cut, with encroachments around the ancient structures being one of the many reasons for the snub.

While official records of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) — the custodian of these monuments — puts the total count of encroachments at 300, TOI’s recent visit to the site indicated that the number could be much higher.

Makeshift settlements

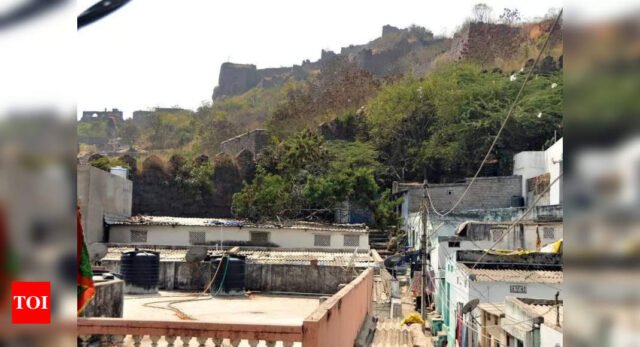

For instance, dozens of makeshift settlements as well as permanent structures were found near the 18 Sidi locality — sticking to the fort’s outer walls. Other areas, like Resham Bagh and the road leading towards Naya Qila, were also lined with rows of modest, closely packed houses with tin roofs compromising the fort’s buffer zone.

The houses even extend into the bylanes. While many of them seem to be old structures, several new constructions too are seen coming up along the hilly stretch — so close to the monument that one can easily jump over to the other side of the fort.

200-m regulated area

The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act mandates a 100-metre no-construction zone around protected monuments and an additional 200-metre regulated area. This rule is also a critical requirement for a Unescotag, as has been mentioned on the Unesco’s tentative list of heritage tag monuments.

Locals claim that there are over 2,000 encroachments around the fort at the moment.

“The entire aesthetic and historical setting of the fort has been destroyed. Encroachments have not only changed the landscape but also made conservation efforts increasingly difficult,” said Anuradha Reddy, convenor of INTACH Hyderabad. She added how such unregulated developments also pose a serious threat to the structural stability of the monument.

Foundation affected

“Illegal constructions often involve digging and drilling into the rocky terrain, weakening the natural foundation of the fort. There have also been instances of waste being dumped along the walls, causing seepage and damaging the fort’s stonework,” Anuradha Reddy added.

Given the seriousness of the issue, activists are now urging the state govt and ASI to take up immediate steps to reclaim the encroached land and implement stricter monitoring systems.

“Most of the settlements there are as old as two decades. And these are not just bastis but huge independent houses, commercial places, roads, temples, mosques etc. We need to carry out a survey to determine the extent of encroachment and the buffer zone before taking any steps. However, the inside parts of the fort are well preserved for visitors,” said an official from the ASI.

The three Qutb Shahi structures have collectively been on Unesco’s tentative list for years now. They have, however, failed to make the final cut, with encroachments around the ancient structures being one of the many reasons for the snub.

While official records of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) — the custodian of these monuments — puts the total count of encroachments at 300, TOI’s recent visit to the site indicated that the number could be much higher.

Makeshift settlements

For instance, dozens of makeshift settlements as well as permanent structures were found near the 18 Sidi locality — sticking to the fort’s outer walls. Other areas, like Resham Bagh and the road leading towards Naya Qila, were also lined with rows of modest, closely packed houses with tin roofs compromising the fort’s buffer zone.

The houses even extend into the bylanes. While many of them seem to be old structures, several new constructions too are seen coming up along the hilly stretch — so close to the monument that one can easily jump over to the other side of the fort.

200-m regulated area

The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act mandates a 100-metre no-construction zone around protected monuments and an additional 200-metre regulated area. This rule is also a critical requirement for a Unescotag, as has been mentioned on the Unesco’s tentative list of heritage tag monuments.

Locals claim that there are over 2,000 encroachments around the fort at the moment.

“The entire aesthetic and historical setting of the fort has been destroyed. Encroachments have not only changed the landscape but also made conservation efforts increasingly difficult,” said Anuradha Reddy, convenor of INTACH Hyderabad. She added how such unregulated developments also pose a serious threat to the structural stability of the monument.

Foundation affected

“Illegal constructions often involve digging and drilling into the rocky terrain, weakening the natural foundation of the fort. There have also been instances of waste being dumped along the walls, causing seepage and damaging the fort’s stonework,” Anuradha Reddy added.

Given the seriousness of the issue, activists are now urging the state govt and ASI to take up immediate steps to reclaim the encroached land and implement stricter monitoring systems.

“Most of the settlements there are as old as two decades. And these are not just bastis but huge independent houses, commercial places, roads, temples, mosques etc. We need to carry out a survey to determine the extent of encroachment and the buffer zone before taking any steps. However, the inside parts of the fort are well preserved for visitors,” said an official from the ASI.