MANCHIREVULA: Hidden behind Forestrek Park in Manchirevula—a hotspot for many govt and private realty ventures of late—is a valley offering a rare glimpse into prehistoric craftsmanship. Scattered here are stone tools crafted by early humans, which archaeologists believe are made of quartzite, serving as testimony to a civilisation that existed between 6,000 and 12,000 years ago.

STOI ventured into the valley, walking through thorny bushes and uneven ground with Omar Ali Khan, associated with World Wide Fund for Nature. He has also found rock paintings at the Forest Trek Park. “What defines this valley is the quartz deposit. Natural fractures are random, but when a rock is manually shaped, you see a distinct sharpness, fine edges, and a taper in one direction.”

The valley has many ancient tools— scrapers, arrowheads, bone marrow breakers, and axe heads. STOI spotted a piece of an axe head, its edges gleaming in the sunlight.

“Prehistoric humans had a technique for securing these tools,” said ecologist Arun Va sireddy, who is researching rocks in AP and Telangana. “They used strips of Palash’s bark—soaking them in water, drying and stretching them before binding the stone to a wooden handle,” he added.

Lost, rusted

Relics from a bygone age: An axe head and an arrow head rock found near Narsingi, Hyderabad

Unfortunately, many of the tools have disappeared over time—thanks to neglect. Experts estimate at least half the wealth here has been lost to trekkers who have taken them away on realising they are ancient tools.

“These tool deposits are rare. Unless authorities officially recognise this as a heritage site and draw up a conservation plan to secure this valley by banning access here, it’ll be gone soon,” said Omar.

Khajaguda

About two years ago, archaeologist Emani Sivanagi Reddy identified a rock shelter amid the expansive rockscape of Khajaguda – sitting in the heart of Hyderabad. At the time he didn’t find any conclusive evidence of human existence, but a chance discovery a few months ago changed that – Neolithic grooves.

When STOI accompanied him there recently, it saw the grooves etched into the rock surface aged between 6,000 and 9,000 years. “These would have been created by early Neolithic inhabitants to sharpen stone tools like axes and celts,” explained Reddy, who previously served in Telangana’s archaeology department for over three decades.

At the lower part of the hill, there were also two water pits, fed by a narrow stream trickling down the rocky slopes. “The water must have flowed through these channels and collected in the pits,” Reddy said.

Trash bin

However, these grooves and pits are now filled with wrappers, cigarette butts, broken glass, and other waste, as visitors treat it like a trash can because of the depression in the rocks. Even the rock shelters are covered with random names and graffiti. Experts claim the shelter is also often used for illicit activities post sunset.

“Such sites hold valuable insights for future generations to understand how early humans lived. They should also be recognised as heritage sites,” said Reddy.

Peerancheru

Peerancheru

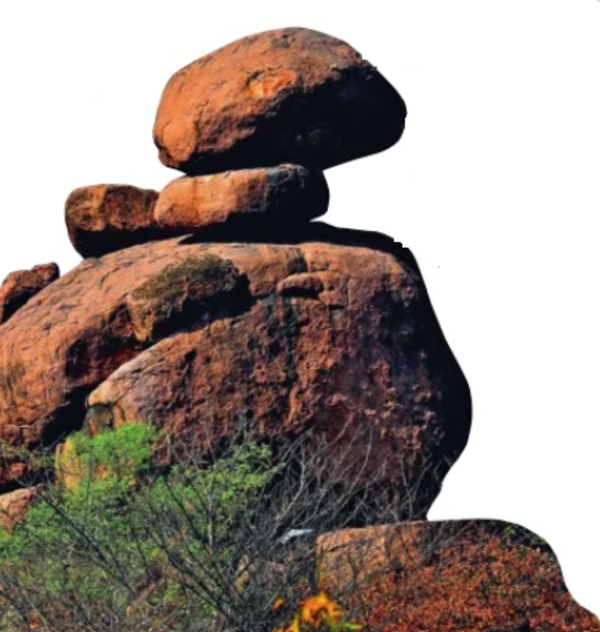

Tucked away in an uphill corner of Peerancheru forest – a 20 min drive from Hyderabad’s IT corridor – are remnants of an ancient civilisation that once flourished in the Deccan region. Estimated to date back 2.5 billion years, a rock shelter here—massive boulders leaning on to each other, forming a canopy-like refuge—carry telltale signs that confirm previous human habitation, say archaeologists.

During a recent visit, STOI also found a pair of ancient stone walls perched on a hill just beside the rock shelter. Built with flattened stones stacked carefully one over the other, it hints at a deliberate effort to create barriers or enclosures. Nearby, an outpost, believed to be 2,000 to 3,000 years old, stands as further evidence of human presence.

“Such arrangements are not natural,” said Vasireddy, who hasdiscovered many prehistoric sites in the Deccan region. “The shape of the rocks, their placement, and the presence of the shelter all point to early human occupation. The outpost suggests this may have been a strategic hiding spot for people seeking refuge.”

Broken, defaced

The site urgently needs protection. Its walls have crumbled due to wear and tear, and the sound of rocks being blasted in its vicinity is a routine affair now. “It might not be long before encroachers lay their eyes on this site,” said Vasireddy.

The damage caused by visitors is another concern. “They scribble on the surface or stand on them, that alters their shape. A protective barrier and signage explaining the significance of the site is necessary to preserve it,” the ecologist added.

Hasmathpet

Close to Secunderabad, the Hasmathpet Cairns is a prehistoric burial ground dating back to the second century BC. Discovered in the early 1900s, the site underwent excavation under Nizams in 1934-35. The cairns are believed to belong to Iron Age tribes that migrated from West Asia, introducing iron technology and horses to South Asia. “Excavations by European scholars in pre-Independence days uncovered a unique burial practice — the deceased were placed in cists (stone-lined graves) along with objects they used in their lifetime. The burial site was then covered with large rocks, marking the graves of these ancient settlers,” said Mohammad Safiullah, founder and managing trustee of Deccan Heritage Trust, which works towards preserving and restoring architectural heritage of the Deccan with help from specialists.

Shrunk, barricaded

This protected heritage site, once home to 2,000 such graves, now lies in shambles. Real estate activity shrunk the site drastically – from 108 acres in 1953 to 30 acres now. When STOI visited the site, it found just two or three graves lying dishevelled. The builders of the towering high-rises around this site have banned access to the graves.