The Indus Water Treaty, signed in 1960, was working despite two wars between India and Pakistan in 1965 and 1971, not to speak of Kargil-like situations on several occasions

Published Date – 24 April 2025, 12:46 PM

In one of the strongest actions following the Pahalgam attack where 26 people, mostly tourists, were gunned down by terrorists, India has said the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) of 1960 with Pakistan will be held in abeyance with immediate effect, until Islamabad credibly and irrevocable abjures its support for cross-border terrorism.

Pradeep Kumar Saxena, who served as India’s Indus Water Commissioner for over six years, said. “This could be the first step towards the abrogation of the treaty, if the government so decides,” he said.

Here’s the detailed article on Indus Water Treaty written by senior journalist and commentator Amitava Mukherjee published by Telangana Today in on March 12, 2023.

(https://telanganatoday.com/rewind-whats-flowing-behind-indus-water-treaty)

Rewind: What’s flowing behind Indus Water Treaty

India has sent a notice to Pakistan expressing its desire to change the dispute resolution system of treaty. Will Pakistan accept it?

By Amitava Mukherjee

Hyderabad: International diplomacy often starts with sending messages. So when India sends a notice to Pakistan expressing its desire to change the dispute resolution system of the Indus Water Treaty (IWT), there is every possibility that New Delhi is trying to convey a message not just to Islamabad but to the world community as a whole as well. After all, the dispute goes much deeper, not the resolution system only. The timing is also significant. India had pushed hard at a time when Pakistan is in turmoil. Similarly, the ruling elite of Pakistan may also take the matter to a high pitch to shift focus from its own inability to rule the country in a proper manner.

The interesting part of the story is that the IWT, signed in 1960, is working despite two wars between India and Pakistan in 1965 and 1971, not to speak of Kargil-like situations on several occasions. So a subterranean spirit of cooperation, of course from the Indian side, is there. It is a bit difficult to explain the Pakistani fear of India’s proposal for a new bilateral dispute resolution mechanism in order to avoid delays in a multilateral approach.

The Treaty

According to provisions of the treaty, Pakistan has 90 days for replying to India’s notice, given on 25 January this year. At the moment, not much activity is seen on the other side of the border. Even the Pakistani media is also unusually reticent on the issue. Through Google searches, I could find only two worthwhile articles by Pakistani columnists in the Friday Times and the Dawn.

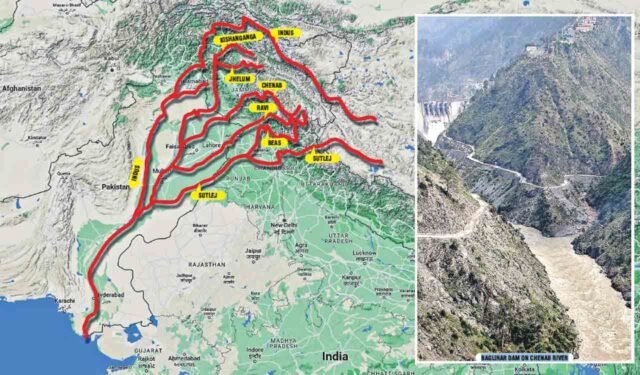

The treaty gives control over the waters of the three ‘eastern rivers’, namely the Beas, Ravi and Sutlej with a mean annual flow of 41 billion cubic metres of water, to India while control over the waters of the three ‘western rivers’— the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab with a mean annual flow of 99 billion cubic metres — is given to Pakistan. Tributaries of respective rivers are also included in this apportionment. India has about 20% of the total water carried by the Indus system while Pakistan has 80%. From this point of view, Pakistan should have no grudge. So where does the problem lie?

The IWT, signed in 1960, is working despite two wars between India and Pakistan in 1965 and 1971, not to speak of Kargil-like situations on several occasions

The Problem

The problem lies in two hydroelectric power plants — Kishanganga and Ratle — that India envisioned on the Indus water system. It has to be kept in mind that the IWT allows New Delhi to use waters of even the above-mentioned west-flowing river systems for non-consumptive uses such as power generation. The Kishanganga hydroelectric project is a run-of-the-river plant in Jammu & Kashmir. The water of the Kishanganga river is first stored in a dam and then diverted to a power plant in the Jhelum river basin. Construction of the project began in 2007 and was expected to be completed in 2016. But in 2011, Pakistan raised objection to it on an apprehension that the project would restrict the flow of the Kishanganga river water in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Islamabad went to a court of arbitration, which, in 2013, ruled that India could divert water for power generation while ensuring a certain water flow to Pakistan.

The Indus Water Treaty stands at a juncture and there is a possibility that the two countries may experience the possibility of a water war

Now the Indus river system is a complex maze of main rivers and their tributaries. While going into the details of the controversy it must be kept in mind that both Kishanganga and Ratle are run-of-the-river type projects where water is released downstream after its use for power generation. These are exactly the types of hydropower stations China is building on the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) river in Tibet. But the Pakistani mind has perhaps been shaped to a large extent by the constant threat of flood the country always lives under and which came true last year. In any hydropower station built on geologically unstable hill ranges, there is a possibility of breach of dams and consequent floods in downstream areas.

The Blame

The Indus Water Treaty stands at a juncture and there is a possibility that the two countries may experience the possibility of a water war with India enjoying a distinct advantage because of being the upstream country. Who is to be blamed for such a situation? Certainly Pakistan, because it had jumped the provisions of the dispute-resolving mechanism contained in the IWT.

As per provisions in the IWT, dispute resolution mechanism has three stages — the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC), neutral experts and the World Bank-mediated Court of Arbitration. At first, Islamabad had opted for the neutral expert option. But within a year after approaching the forum, it suddenly changed its mind and sought arbitration proceedings. Here, New Delhi put its foot down. Its considered opinion is that Pakistan is intentionally trying to internationalise the issue. So India went ahead, completed the construction and then commissioned the Kishanganga hydropower project in 2018.

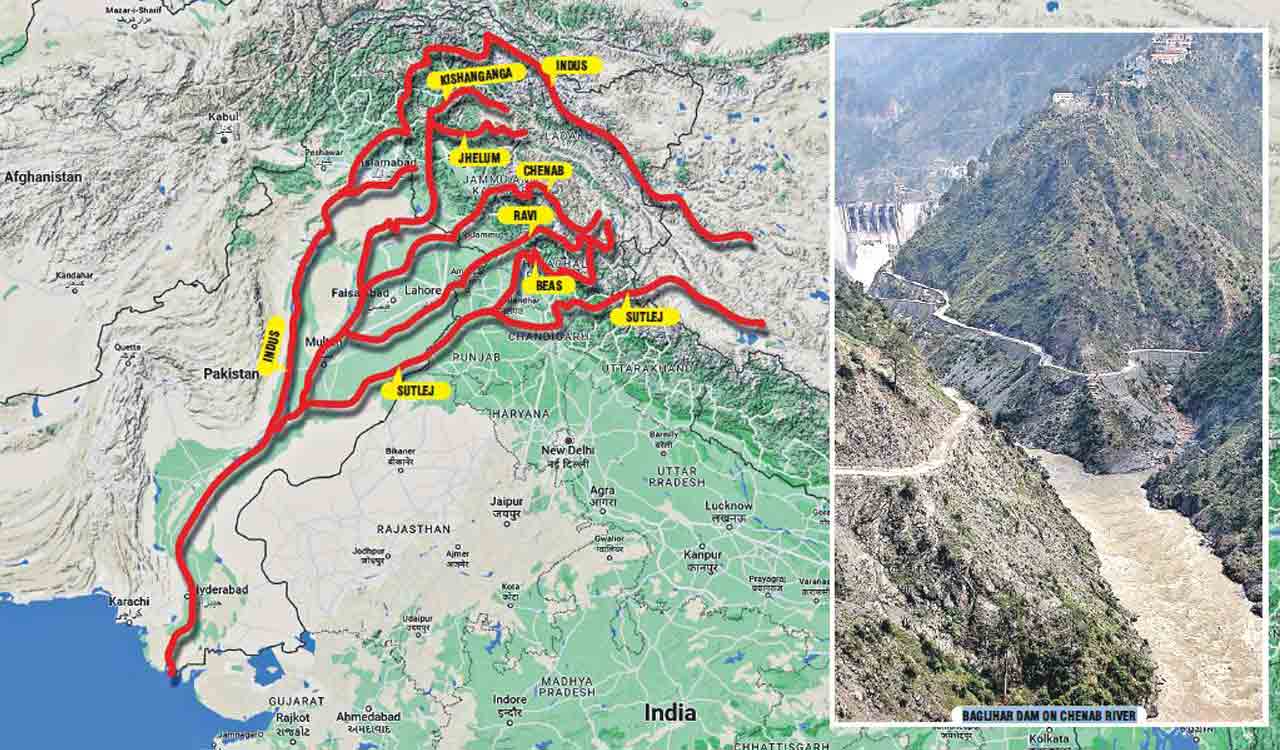

The Ratle hydroelectric plant is under construction over the Chenab river in Jammu and Kashmir. These two are not the only apples of discord between the two countries. There is the Baglihar hydroproject over the Chenab river. This one has also come up brushing aside Islamabad’s objection as Pakistan has not been able to substantiate its protests in the context of IWT provisions.

Thus far it was a matter of technological questions. India is the upstream country even in the matter of the ‘west flowing’ rivers. The IWT has recognised it and given New Delhi the elbow room to use waters of the ‘western rivers’, but moving within the constraints of the IWT guidelines. However, now the matter has shifted from the controls of engineers to that of geostrategic planners and politicians.

In 2011, Pakistan raised objection to India’s Kishanganga project on an apprehension that it would restrict the flow of the Kishanganga water in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir

In 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that India would stop ‘every drop’ of water from Ravi, Sutlej and Beas — the three eastern rivers assigned to India — from flowing to Pakistan. In the aftermath of the Pulwama terrorist strike, Nitin Gadkari, another Union minister and BJP leader, had said that all water flowing from India will be diverted to Indian States to punish Pakistan. Rattan Lal Kataria, then central minister, had said that ‘every effort is made’ to stop the flow of water downstream from the three rivers assigned to India.

The Approaches

What will happen if Pakistan sends no reply even after the 90-day deadline? Perhaps it will, stressing its commitment to the existing treaty because it gives Islamabad an avenue to internationalise the issue and seek help from international friends. Here lies the basic difference in approach between the two countries. Pakistan is always under a perceived threat from its big and powerful neighbour. This acted behind its attempt to internationalise the Kashmir issue. Even during the 1965 and 1971 wars, Pakistan always looked towards the US and China as two crutches. In 1971, this attitude of Pakistan had goaded India towards seeking help from the then Soviet Union. The same mentality is now in operation in Islamabad.

So far as the BJP’s concept of nationalism is concerned, there is every possibility that the Union government in Delhi will take a hard stand. Resolving and refashioning the dispute mechanism system may be the first step. Possibly the Union government will not act till the G20 summit, slated to be held in New Delhi, is over. But one thing is certain: the BJP is all for scoring a victory over Pakistan, even going so far as to the abrogation of the IWT altogether. For this, it may even be prepared to risk international embarrassment too.

For the government of Shehbaz Sharif in Pakistan, it is really a difficult situation. It cannot agree to the Indian proposal, lest the government there should face public condemnation. On the other hand, if it cannot stop India from going ahead, Shehbaz Sharif’s days as Prime Minister of Pakistan are numbered.

The strategic importance of the Indus river system gives it a unique character in South Asian geopolitics. It will not be an exaggeration to say that the Indus river system is the lifeblood of present-day Pakistan and any situation leading to a threat to its existence can bring about serious consequences in sub-continental geopolitics. Its floodplain where most of Pakistan’s population live is one of the largest agricultural regions in Asia. It must be remembered that Pakistan is still a predominantly agricultural country with a fair mix of tribal cultures. According to Climate Diplomacy, a scholarly journal, around 90% of Pakistan’s food and 65% of its employment depend on farming and animal husbandry which are sustained by the Indus river system.

Pakistan should realise that it is not in a position to indulge in any game of one-upmanship. Right from the beginning, India always favoured the Permanent Indus Commission as the preferred tool for dispute resolution, a bilateral approach to say the least. Clinging to this method would have created more mutual trust. Islamabad’s approach to an internationally mediated tribunal has produced just the opposite result.

Here Pakistan’s foreign policy establishment has failed the country. It should have kept in mind that India has several river basins which make food production in the country resilient whereas Pakistan has only the Indus. This has made the Indus basin the world’s second most overstressed aquifer. As per calculations given by Climate Diplomacy, total water demand in Pakistan is likely to increase from 163 cubic kilometres in 2015 to 225 cubic kilometres in 2050 with groundwaters in river basins depleting very fast due to over-exploitation.

Pakistan cannot fault the present Indian ruling establishment if the latter decides to use water as a weapon against Pakistan-sponsored terrorist activities in different parts of India, particularly Jammu & Kashmir. That India has acted within the stipulations of the IWT becomes amply clear from the fact that on earlier occasions also Pakistan’s complaints have been dismissed by the competent international authority.

It should also be remembered that not just Pakistan but also a certain stretch of India like Gujarat forms downstream areas of the Indus system and here Pakistani activities, in collaboration with the World Bank, have harmed Indian interests. This has happened in the Rann of Kutch where the Indus flows before emptying itself into the sea. In violation of the IWT, Pakistan, with the help of the World Bank, has constructed an outfall drain that diverts the saline and polluted water flowing into the Indus delta of Pakistan and directs it to the sea through the Rann of Kutch. This not only gives rise to floods in the Rann of Kutch of Gujarat but at the same time also pollutes and contaminates waters used by local salt farms.

For a long time, the IWT was the only stable area in otherwise wholly unstable relations between Pakistan and India. But now there are dangerous portents here too.

(The author is a senior journalist and commentator)